Second Intermediate and New Kingdom of Egypt: A Journey of Discovery

- Jun 2, 2024

- 10 min read

[This is a lecture written for the course 'HIST 262: History of the Ancient Near East,' taught Fall 2023 at God's Bible School and College, a regionally accredited College in Cincinnati, Ohio. Bibliographical material will be posted under Research on this site.]

The Second Intermediate Period

Because of the chaos that is the Intermediate Periods, the Second Intermediate Period consists of confusing and overlapping dynasties, including the Fourteenth through the Seventeenth Dynasties, where the Seventeenth Dynasty is the only one with a coherent king list (Beetz 2008: 393). Some scholars include at least the late Thirteenth Dynasty to this period and exclude the Fourteenth altogether (Quirke 2015: 18). Interestingly, it is not only modern histories who become confused at this point. Of note, a king’s list from a temple at Abydos dating to the Nineteenth Dynasty’s Sety I ignores the kings of both the First and Second Intermediate periods and any kings who were considered illegitimate at the time (Bard 2015: 40). For the purpose of this study, it will be assumed that the Second Intermediate period extends from the Thirteenth through the Seventeenth Dynasties (David 2003: 58).

It should be pointed out that the Egyptians created something of a canonical past for themselves, as they looked to the past for both authority and authenticity; King Neferhetep of the Thirteenth Dynasty can be seen in an image piously studying at ‘the house of writing’ attempting to discover how to properly create a statue for Osiris (Kemp 2006: 68). Because of this rather canonical nature of the past, those who deviated from the norm, such as during the Intermediate Periods, were excluded from the canon altogether.

Dynasty Confusion.

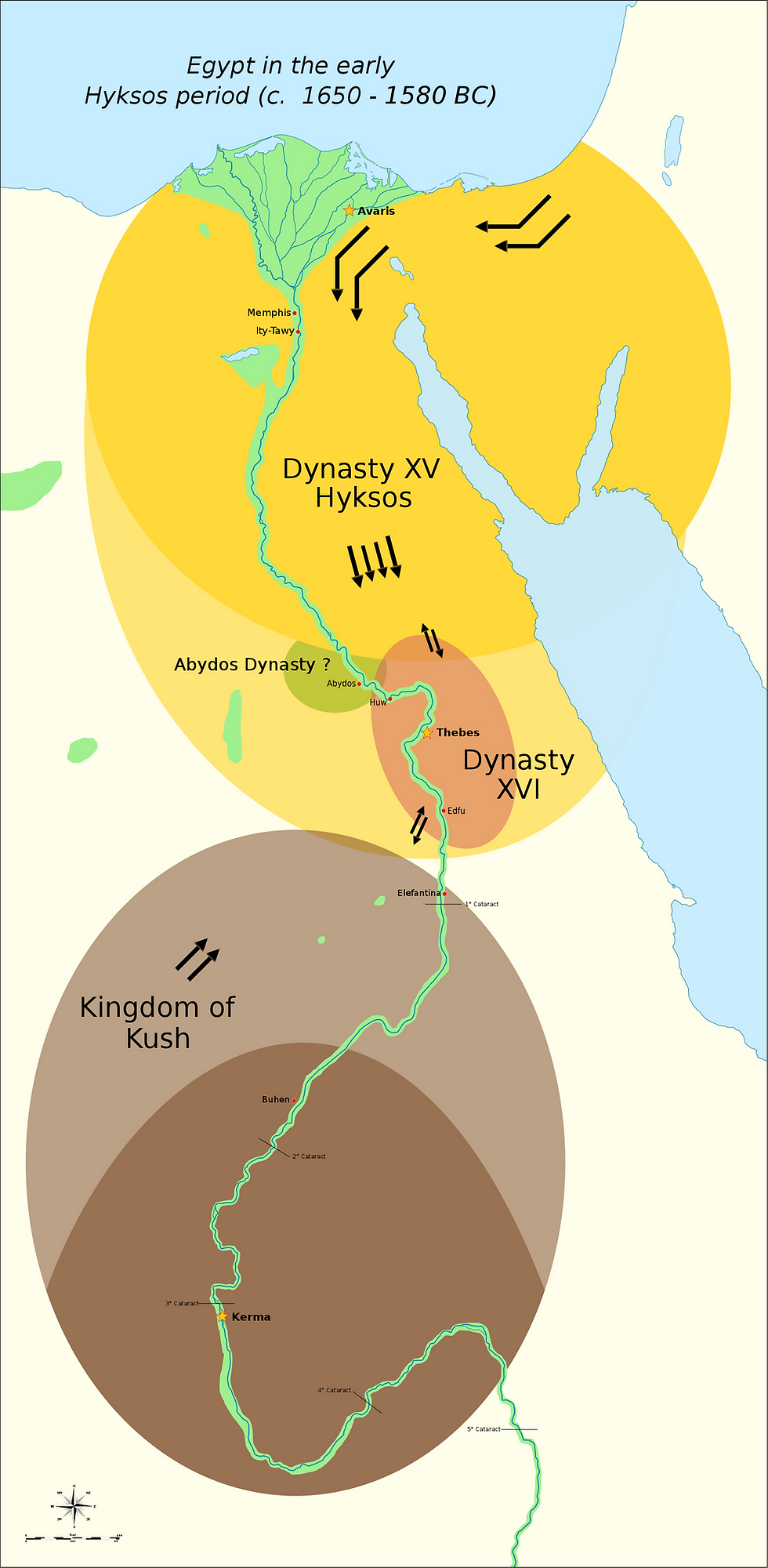

At some point during the Thirteenth Dynasty, Egypt began to fall apart. Internal collapse occurred with a rapid succession of rulers who attempted, but failed, to hold the kingdom together (David 2003: 86). Because of their failure, control of the kingdom fell into multiple regions, causing an overlap of dynasties. The Thirteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties ruled in the south, consecutively, and the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth Dynasties all shared power in the Nile Delta, the latter two being foreign rulers (Mieroop 2011: 45).

Sixty kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty continued to rule from Thebes, while simultaneously seventy-five kings of the Fourteenth Dynasty ruled in the Delta; the foreign Hyksos make up both the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties of foreign rulership, while the Seventeenth Dynasty is founded at Thebes during the end of the Thirteenth (David 2003: 65). Notably, from the earlier periods of the Thirteenth Dynasty was found a papyrus that listed the names of ninety-five slaves likely belonging to the Vizier Resseneb; the greater majority of these names are listed along with the moniker ‘Asiatic’ (Kemp 2006: 28).

Asiatics/Hyksos.

The Asiatics who began entering the Delta and eastern Nile banks since the Old Kingdom (Brovarski 2005: 47), who had made their home these regions, began rulership of their own regions in Lower Egypt as the kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty could no longer maintain power. These Asiatics are known today as Hyksos (David 2003: 65), a Greek term derived from the Egyptian meaning ‘princes of foreign countries’ (Gates 2011: 101). The Hyksos were not invaders moving into the land but rather people from the Southern Levant who had moved into Egypt previously (Bard 2015: 188), likely seeking reprieve from Levantine famines, carrying Levantine culture with them (Cohen 2016: 6). Perhaps the most well known family to have entered Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and remained throughout the Hyksos period is that of the Biblical Jacob.

It should be noted that this ‘Hyksos’ period was not a period of greatness in Egypt (Aling 2002: 22), though trade between the Hyksos capital of Avaris and the Southern Levant persisted in abundance (García 2014: 249). A Herakleopolitan king explained that the arrival of the Hyksos came at a time of civil war in the land, when the security of the people was lacking (Wilson 1951: 111).

The Hyksos controlled territories from the Delta up to Hermopolis in Middle Egypt, though some within this region were also controlled by lesser Asiatic groups, making up the Sixteenth Dynasty, and by Egyptian vassals (Murnane 1995: 702). They somewhat continued Egyptian administration tactics, used Egyptian writing, and engaged Egyptians in their service (Bard 2015: 216). The Hyksos rather strongly Egyptianized themselves, possibly in an attempt to legitimize their authority (Morenz and Popko 2010: 104).

Ultimately, the Hyksos made Upper Egypt pay tribute to their power (Moers 2010: 700), an army, ships, and even foreign connections facilitating their expansion as marauding troops even more so destabilized the already destabilized regions (Bietak 2005: 57-58).

The outside connections held by the Hyksos included, of course, the Levant (García 2014: 249), but also Cyprus, and even Crete as evidenced by Hyksos artifacts discovered at Knossos (Bietak 2005: 58). Interestingly, it was the Hyksos who introduced the horse and chariot into Egypt, possibly as early as the Middle Kingdom (cf. Aling 2003: 11), as well as the composite bow and vertical loom (Gates 2011: 101), and they began to blend together Canaanite worship with Egyptian, equating the god Seth with the god Ba’al, and introducing Astarte and Anat into Egypt (Pinch 2002: 18).

The Fall.

During the Seventeenth Dynasty, Theban kings fought back against the Hyksos, some possibly even dying in battle (David 2003: 65). Under Seqenenre Tao II, the Thebans pushed northward in an attempt to recapture Egypt (Moers 2010: 700). Although relations with the Hyksos were said to be good at the time (Mieroop 2011: 181), Seqenere’s successor, Kamose, continued the fight against the foreigners (David 2003: 65). Ultimately, it was Ahmose, successor of Kamose and founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty, who expelled the Hyksos from the lands (Mieroop 2011: 182) and followed them into the Southern Levant, laying siege to a fortress there (Bard 2015: 227).

The New Kingdom Period

The New Kingdom begins with the expulsion of the Hyksos and the destruction of any residual power bases in the Southern Levant that remained (Lloyd 2010: xxxvi). The Eighteenth Dynasty reconquered and reestablished a unified kingdom, moving the capital back to Memphis (Bard 2015: 227). Surprisingly for a time from so long ago, the period is well documented (Morenz and Popko 2010: 101).

This new period in Egyptian history is one of an Egyptian empire, their power spreading beyond historical Egypt (Bard 2015: 38). The Hyksos Period forced the kings to adopt a rather aggressive foreign policy (David 2003: 89), and although not organized as an Egyptian province, the Egyptian kings held sovereignty over several Levantine city-states (Morenz and Popko 2010: 101). They pushed deep into Nubia and reestablished old, Middle Kingdom fortresses (Gates 2011: 102), and they reopened old trade routes, including into the rather remote land of Punt, likely somewhere along the eastern horn of Africa (Gates 2011: 102), where the typical goods were spices, resins, ivory, baboons, perhaps slaves, and more (Fattovich 2005: 774).

A Time of Innovation and Slavery.

The skills and techniques that the Hyksos utilized in war, concepts adapted from the north, were further adapted by the Theban kings to lay the foundation of what would be the Egyptian Empire of the New Kingdom (David 2003: 89). Though the Eighteenth Dynasty kings generally followed older kingship patterns, kingship itself went through an innovative stage; one aspect of this innovated stage was the increasing direct military leadership, establishing warrior kings upon the throne (Morenz and Popko 2010: 106).

Another military innovation was that of the war chariot. It was only after the Second Intermediate Period that the Egyptian army introduced chariotry for use in war, another concept adapted from the Asiatics (Mieroop 2011: 167). As a matter of fact, before that point, wheeled vehicles generally did not exist in Egypt, as they had little use for them—the Nile providing a better system of transportation (Partridge 2010: 381).

Innovations were also made in the realm of literature. While older genres of literature continued into this period, such as autobiographies, annals, and hymns, two new styles of poetry emerged: the love poem and the epic poem (Reed 2008: 646). Some examples of love poems include lyrics to be recited at banquets with dancing imagery, and others include invocations of Hathor, goddess of love, in order to secure a young man’s perpetual love (Noegel 2006: 399). Epic poetry, such as the Prayer of King Ramesses II, records poetry in narrative form (Reed 2008: 646). In the Prayer of King Ramesses II, the king recants his deeds as evidence that the deity, Amun, should supply help in the battle of Kadesh, listing building projects, trade relations, and more (Foster 2002: 123). Of note, the Dynasty Eighteen rulers attributed much of their successes, including the expulsion of the Hyksos and military campaigns in the Levant, to Amun (David 2003: 90).

Grave robbing had occurred throughout history, and most of the Old Kingdom pyramids were likely looted during the First Intermediate Period (Bard 2015: 37). Because of this, the burial of the kings had moved away from huge pyramids, which did little more than act as large billboards advertising the location of wealth, to what is known today as the Valley of the Kings. The area was isolated but near the capital, and the kings were buried in deep rock-cut tombs, later in the New Kingdom to be accompanied nearby by deceased queens and princes (David 2003: 90). Of course, this isolated location did little to stop grave robbers, many of these tombs being opened and robbed during the Twentieth Dynasty (Bard 2015: 37).

As the Egyptian empire developed, an abundant commodity was introduced: the slave. Slavery in Egypt, though originating earlier, is seen in the capturing of prisoners of war who were enslaved dating back to the Old Kingdom (Loprieno 2012: 5) and, slavery was well known to have occurred in the Middle Kingdom period (Aling 2002: 23), but with a growing international interest during the New Kingdom, large numbers of slaves were procured through warfare (Lesko 2005: 911), from both Nubia to the south and the Southern Levant in the east (Loprieno 2012: 12).

Of particular interest to this study, Canaanite slaves appear to have been used as a labor force in the turquoise and copper mines at Serabit el-Khadem in Sinai, who during the off-season likely resided in the Delta (Wilson, 1951, p. 191). In fact, Egypt became quite exposed to Canaanite culture, language, and religion; not just from those enslaved but also from free couriers and merchants (Ahituv 2005: 218). It should be noted that the presence of slaves, though understood, is underspecified in New Kingdom texts (Loprieno 2012: 12).

The site of Tell el-Daba/Ezbet Helmy was the site of a major naval base in the early New Kingdom (Bard 2015: 235) referred to as Perunefer (Bietak 2009: 3), but referred to later in history as Piramesse or Pi-Ramesses (Cline 1998: 201). Here, the presence of Canaanite cultic materials has been found (Bietak 2009: 15), including iconography of the god Seth/Ba’al (Bietak 2009: 3). This sea port was likely one of the two store-cities, Piramesse, that was built by the Hebrew slaves mentioned in Exodus 1:11. This site was quite important under Thutmose III and Amenhotep II, but there is a lack of records referring to this site again until the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (Bietak 2018: 223).

The condition of slaves during this New Kingdom period is not very pleasant. Although not directly referred to as ‘slaves,’ the Satire of Trades, an early New Kingdom text praising the advantages of being a scribe, lists several of the disadvantages of being a slave, including not benefiting from one’s work and receiving fifty lashes for not being able to work (Loprieno 2012: 2).

Akhenaten and the Amarna Period.

Toward the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Egypt entered something of a parenthetical period where a king, Akhenaten, sometimes referred to as the heretic king (Rea 1960: 64), established a new cult worshipping Aten, the sun-disk deity (Bard 2015: 240). This may have been a dismissal of the Egyptian pantheon in order to worship just one deity (Millard 1994: 122) or a form of henotheism where one god is worshipped above others, particularly as representations of Amun were destroyed or erased, but other deities did not suffer the same fate (Krauss 2000: 96). Either way, the king changed his name from Amenhotep to Akhenaten in order to honor his deity, and later Egyptians did not accept this (Bard 2015: 240).

The king moved the capital to Amarna in Middle Egypt and appears to have been far too engrossed in the construction of the capital and his religion to care for international affairs (Rea 1960: 64). As evidenced from the Amarna Letters, a group of cuneiform communications sent to the king (Liverani 2005: 150) from the Southern Levant, Akhenaten appears to have been indifferent to the fact that Egyptian control in the Levant was disintegrating (Wilson 1951: 256). It is also possible that the lack of interest in the region was due to Hittite superiority (Liverani 2005: 152), particularly as the Hittites had just recently defeated the Mitanni Empire who were allied with Egypt (van Dijk 2003: 278). The kings of Egypt during this period had found it difficult to maintain the empire so far away (Gilbert 2008: 95).

Ramessides.

From Akhenaten onward, the Eighteenth Dynasty had lost its power. Ultimately, the Nineteenth Dynasty would restore that power, stabilizing the kingdom once again (Dodson, 2013: 154), ushering in the Ramesside Period (Wilson 1951: 129).

Major shifts in Egyptian society occurred between the Old Kingdom and the Eighteenth Dynasty; by the end of the Middle Kingdom, the vizier dominated the central administration of the land (Cruz-Uribe 1994: 50). Under Thutmose III in the New Kingdom, the vizier’s wide-ranging duties included the regulation of the army, most likely a reaction to the previous Hyksos ‘invasion’ (Cruz-Uribe 1994: 50), the administration of maritime forces and fortresses, and even control over the cutting down of trees (Gilbert 2008: 21). During the later periods of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the vizier appears to have had more control than the king himself (Cruz-Uribe 1994: 50).

At the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the vizier of the boy king, Tutankhamun, became king (Kawai 2010: 289). This would appear to make a major change in Egyptian royal succession as during the Nineteenth Dynasty the title appears to have become mandatory to legitimize kingship (Kawai 2010: 268).

During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, known as the Ramesside Period, Egypt, once again, faced a threat from foreign forces, including repelling a Libyan invasion (Gilbert 2008: 52). Hittite power also threatened Egypt, until a treaty could be made; later, the attempted invasion of the Sea Peoples and their subsequent invasion of the Levant diminished the Egyptian kings’ desire for expansion (Xekalaki 2021: 3946). That said, by the Ramesside Period, the ideal of peace through victory included essential elements of loyal foreigners (Kemp 2006: 43), Egypt becoming much more pluralistic at this time than any point previously (Xekalaki 2021: 3945).

The end of the Ramesside Period, and the New Kingdom itself, was marked by short reigns and political unrest (Morenz and Popko 2010: 119), the influence of the Twentieth Dynasty dying out with the death of the last king, Ramesses XI (Naunton 2010: 121). Upper Egypt began to revolt (Murnane 1995: 709). The rebels pushed out the High Priest of Amun, and villagers at Deir el-Medina went on strike (Morenz and Popko 2010: 119) and looted tombs for precious goods (Yurco 2005: 295). Ultimately, the Ramesside power over Upper Egypt was lost, being replaced, instead, with a usurper as high priest; eventually, Libyan immigrants in the north came to power over the Lower Kingdom, beginning the Third Intermediate Period (Morenz and Popko 2010: 119).

Check out the Bible Land Explorer!

Comments